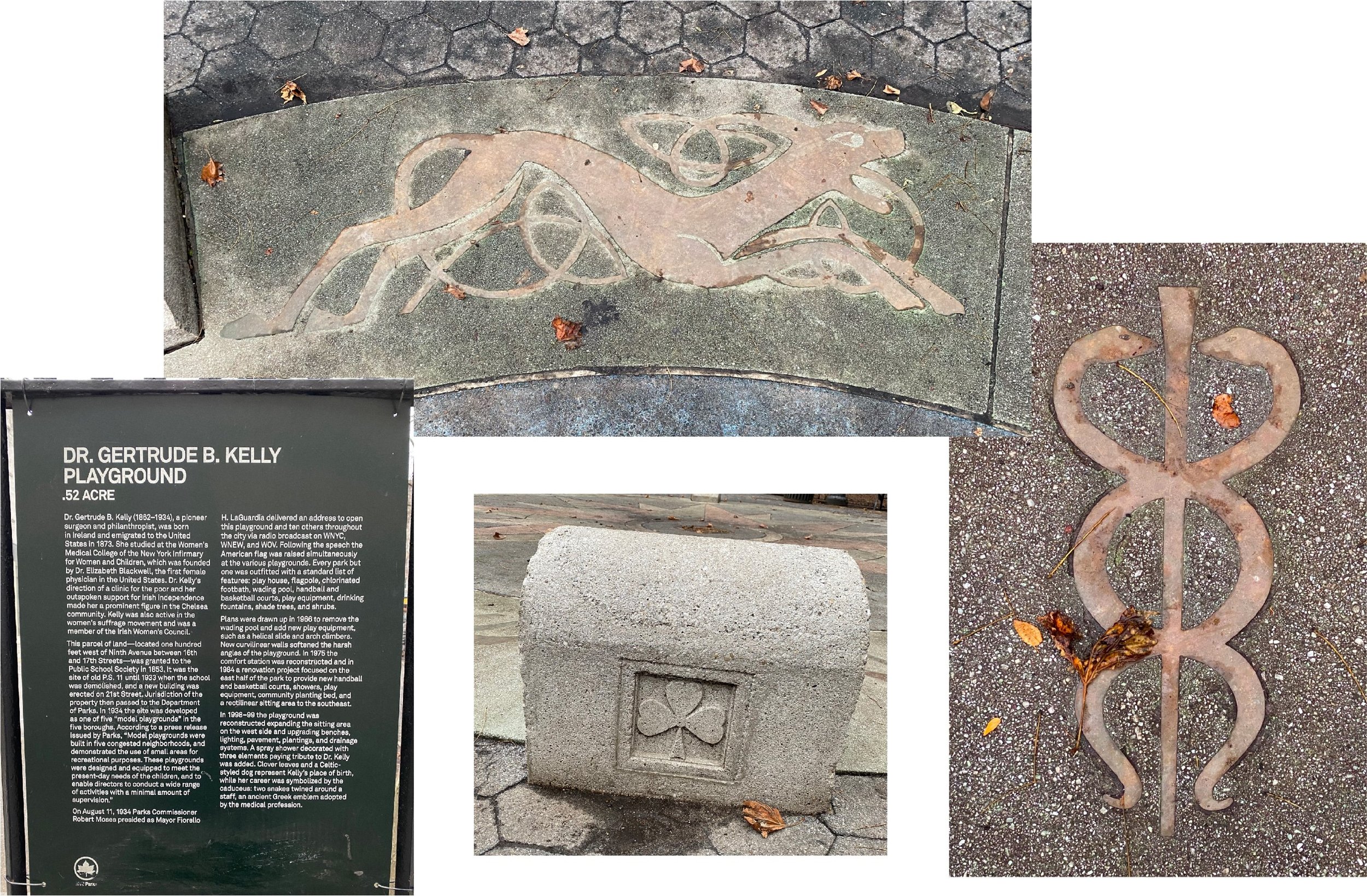

There is a public park on 16th Street just West of Eighth Avenue in Chelsea in New York City. It is named the Dr. Gertrude B. Kelly Playground, one of five model playgrounds built by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses in 1934, and dedicated to the memory of Dr. Kelly by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia on May 16, 1936. The playground is decorated with four-leafed clover leaves and a Celtic-styled dog, and the caduceus, representing the Irish origins of this New York physician.

Gertrude Kelly had died two years previously in 1934, and New York City was honouring her with a playground named in her memory. Her story is that of an extraordinary Irish immigrant physician and an outspoken, courageous activist.

* * *

Gertrude Brice Kelly, known as Bride to her friends, was both in 1862 in Ireland, in Carrick-on-Suir in Co. Tipperary, the South-Eastern corner of the county, with the borders of counties Waterford and Kilkenny a few miles outside of town. Her parents were Jeremiah Kelly and Kate Forrest, teachers by profession. It is likely that Jeremiah and Kate’s involvement in the Fenian movement prompted the family to emigrate to the United States in 1868, a year after the Fenian rising, when Gertrude was 6 years old. The family settled in Hoboken, New Jersey, where her father became a principal in a public school.

Of her nine siblings, little is known about them with one notable exception. Her older brother John Forrest Kelly received his PhD from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, becoming an assistant to Thomas Edison. His career was marked by his leading role in alternating current technologies, developing over 70 patents. He became very active in the cause of Irish nationalism, contributing financial resources and writing extensive political commentary.

Gertrude, younger by 3 years, initially followed her father into teaching in the New Jersey public school system but then she followed John into third level education, enrolling in the Women’s Medical College in New York, the Medical School founded by Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to practice medicine in the USA, who had also started her career as a teacher. New York Presbyterian’s Lower Manhattan Hospital remains at the site of the Women’s Medical College in New York, at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge. Kelly graduated with her M.D. degree at the age of 22, and became a surgeon, continuing to operate for over 30 years at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, an institution also founded by Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell. The building still stands at the corner of Crosby and Bleeker Streets in Noho.

Kelly’s medical practice was focused on serving the disadvantaged, in the slums of Newark in New Jersey, the tenements of the Lower East Side in Manhattan, and her medical clinic in the Chelsea neighbourhood of Manhattan.

Her medical work was entwined with her political activism. She declined to regard sex workers as “fallen women”, but as economic victims, writing the essay “The Root of Prostitution” in the magazine Liberty that women chose the sex worker profession because they could not make an adequate living through respectable forms of labor. She wrote “We find all sorts of schemes for making men moral and women religious, but no scheme which proposes to give woman the fruits of her labor”. She also expressed nuanced views about feminism, writing that “there is, properly speaking, no woman question, as apart from the question of human right and human liberty” and that “The woman’s cause is man’s—they rise or sink/Together,—dwarfed or god-like—bond or free”. To Kelly, gender was less important than “universal liberty, equality of rights, individual responsibility” as “the moving principles of societary progress”.

Dr Gertrude B Kelly Playground, 16th Street and 8th Avenue, New York City .

Kelly was, like her brother and parents, deeply committed to Irish nationalism. She was elected the first President of the Cumann na mBan (The Women’s Army) branch in New York city in 1914, the year she made a donation to the Republican cause with the hope that it would purchase “$100 worth of bullets for the friends of Queen Mary who may try to defeat the cause of political liberty”. She helped with the US fundraising that was ultimately used for 1916’s Easter Rising in Ireland, and subsequently the funding of the families of the thousands of imprisoned Irish Volunteers.

Her boldest strokes were in 1920, when she followed the organization of a blockade of the British embassy in Washington DC with a strike at a Chelsea pier in Manhattan directed at British ships. The instigators of the strike were Kelly and other women, including Leonora O’Reilly, Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington, and Eileen Curran of the Celtic Players. They dressed in suffragette white, with green capes, carrying signs reading “There Can Be No Peace While British Militarism Rules the World”. The strike was joined by Irish longshoremen, Italian coal passers, African-American longshoremen, and workers on a docked British passenger liner, spreading from Chelsea to Brooklyn, New Jersey, and Boston.

Dr. Kelly became a required visit for every Irish political and literary visitor to New York. While she claimed to have been a member of almost every Irish association in New York, as a woman she would not have been invited to join the men-only New York Celtic Medical Society of the time. An atheist, she described herself as an unredeemed pagan. She was legendary in the Chelsea community for her practice during house calls to her impoverished patients of refusing payment, instead surreptitiously leaving $5 under her dinner plate to be discovered after her departure. In 1929, she was badly injured in a car accident and became an invalid. A reception was subsequently held in her honour at the Hotel McAlpin, attended by over 500 representatives of medicine, law, social services, labour, women’s suffrage movement, clergy and city officialdom. She died four years later in 1934 at the age of 72, survived by her long-term partner Mary Walsh. The Irish Government was represented at her funeral. The playground in Chelsea honours the memory of a groundbreaking Irish woman physician, social activist, writer and benefactor.